-

Takeaways for Decision Makers From Turbulence to Transformation: Navigating Challenges Towards Action on Transport, Climate and Sustainability

This document outlines a critical overview of key trends, challenges and opportunities in the intersection between transport, climate and sustainability. It aims to provide food for thought and action in support of decision makers interested in advancing the transformation towards sustainable, low carbon transport.

Efforts to achieve climate and sustainability goals are derailing in a world of accelerating interconnected crises

The world experienced significant challenges and major crises during 2021 and 2022, including the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine; this was followed by global economic downturn, further disruption of supply chains and the ongoing energy crisis. The year 2023 has added record-breaking heatwaves and the hottest July in modern history, record ice loss in Antarctica and Greenland, and other extreme weather events attributed to human-caused global warming. Beyond the often devastating human toll, these events have had a substantial impact on transport globally. They have exacerbated ongoing challenges in the sector, increased uncertainty, and revealed vulnerabilities, resulting in a general downgrading of the urgency of climate and sustainability concerns.

The transport sector has been a major contributor to the rebound in fossil fuel consumption since the height of the pandemic in 2020 and 2021. Most places have experienced a return to pre-pandemic traffic congestion and air pollution, while air travel also has increased. Public transport suffered a large blow early in the pandemic and still has not fully recovered, as transport operators struggle to maintain operations. During the first year of the pandemic, urban dwellers in some areas moved away from city centres, particularly in high-income countries, contributing to urban sprawl. While the overall size of vehicles grew 7% on average between 2010 and 2019, since the onset of the pandemic some vehicle models have increased massively in size, growing nearly 30% just between 2020 and 2021.

The transport sector has experienced some enduring behaviour changes, affecting overall sustainability. In some places, city centres continue to see less footfall, while in other places city centres are bustling as much as or more than pre-pandemic levels. The rate of improvement of road safety leading up to 2020 was far below the targets set under the United Nations Decade of Action for Road Safety, and in 2022 road deaths globally increased 10% compared to 2021, reaching record levels in the United States due in part to decreased traffic enforcement.

Active travel such as walking and cycling seems to have benefited from behavioural changes instilled during the pandemic. The unprecedented rapid development in supportive infrastructure and policies – such as “pop-up” bike lanes, pedestrianising streets, and removal of on-street parking in many cities – has increased space for people rather than cars. Similarly, the use of shared mobility has continued to increase in many places – due in part to people moving away from public transport during the pandemic and from personal vehicles experiencing rising fuel costs – although it remains minimal relative to overall vehicle use.

On top of the impacts of the pandemic, the Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 exacerbated major existing crises and challenges. Beyond the immediate humanitarian and social impacts, the invasion contributed to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, originating from the rebuilding of civilian infrastructure as well as from fires, fossil fuel pipeline leakages, warfare and refugee movements. The loss of transport and other infrastructure in Ukraine has been significant, including damage to the country’s railway network; meanwhile, the rerouting of flights due to airspace closures has led to longer flight times and to an increase in related emissions. Ongoing supply chain issues have exposed the fragility of global supply and logistics chains and their international interdependencies.

The invasion led to an energy crisis, with fuel prices in many countries doubling in June 2022 compared to a year prior. This placed a strain on vehicle drivers and freight operators while leading to record profits for oil companies and contributing to higher subsidies in some places to support individual car travel. The high fuel prices also exacerbated inflation globally, on top of the rise in food prices following the disruption of key grain supplies and exports from Ukraine, which has contributed to a food crisis, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

Spurred by the geopolitical instability, the energy crisis catalysed a renewed determination to increase energy independence. Governments and industries alike have recognised the need to maximise resiliency and minimise potential future shocks by reducing their reliance on fossil fuel imports. In some places, this has meant greater support for renewable energy, energy efficiency, and energy conservation, although many countries also have pushed for additional domestic fossil fuel production and infrastructure to support imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG).

Amid these challenges, progress towards global targets for increased climate action and sustainability has been jeopardised. In 2023 – the halfway point between the 2015 adoption of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and their target year of 2030 – it was estimated that none of the 17 SDGs would be met in their entirety, and that only 12% of the SDGs’ targets would be achieved. This includes several SDGs related to the transport sector, such as SDG 3 (good health and well-being), SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy), SDG 9 (industry, innovation and infrastructure), SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities) and SDG 13 (climate action). Efforts to achieve a just energy transition also have seen little progress, despite being increasingly acknowledged at the global level.

As the laggard among sectors, transport had the highest increase in global emissions.

Hopes that the COVID-19 recovery packages would be used to support low-carbon transport proved to be wrong, as most recovery funding for transport went to road expansions, airline bailouts, and other less sustainable ventures. Meanwhile, the global transport system has been allowed to grow unabated despite the high potential to advance sustainability and address climate change. Even in a low-carbon pathway, transport is projected to be the second highest emitter of carbon dioxide (CO₂) among energy end-use sectors (after industry) by 2032, and the highest emitter by 2050, due mainly to long-distance air travel.

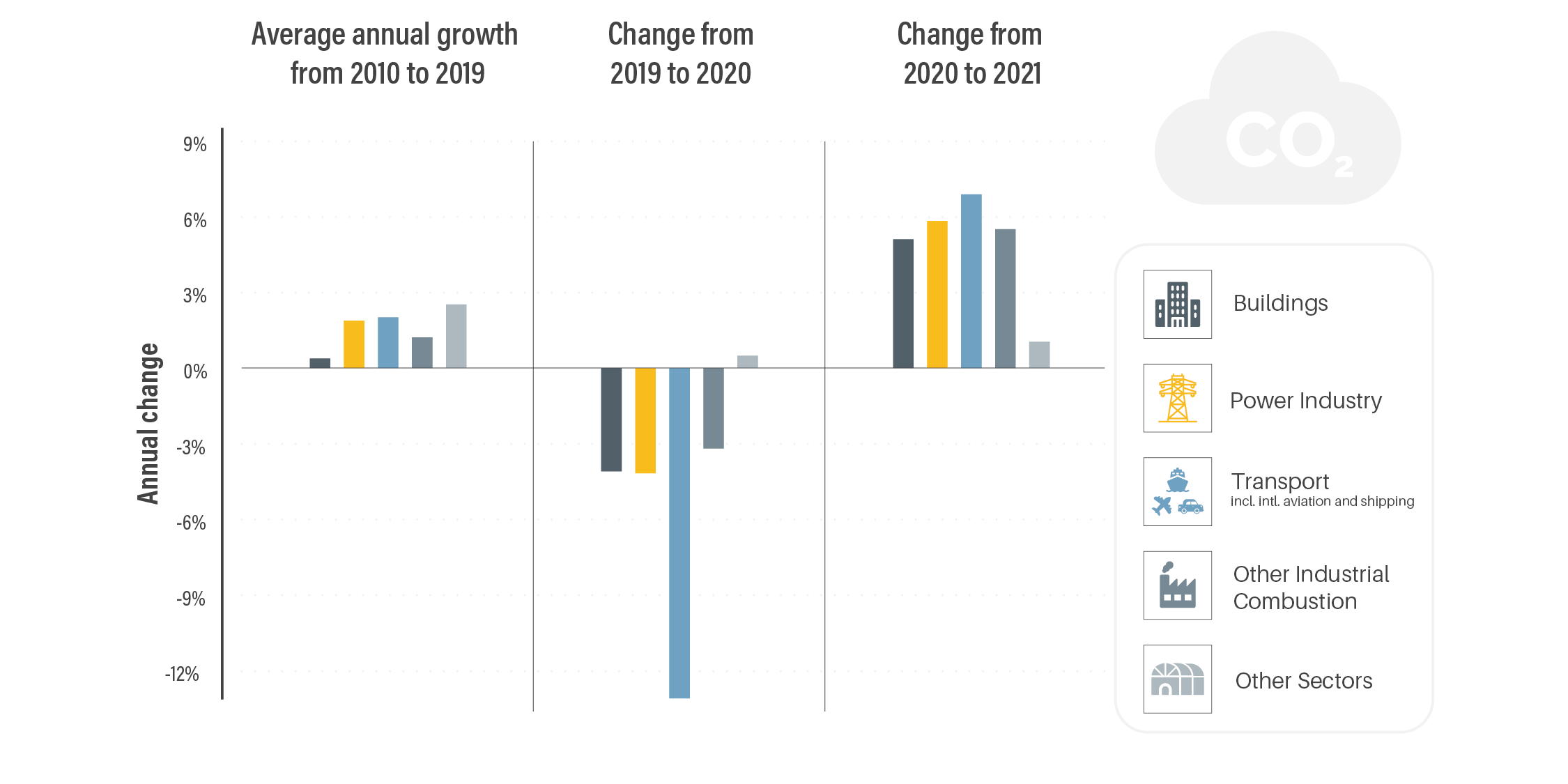

Transport has experienced the fastest growth in CO₂ emissions among combustion sectors, with global transport emissions rising 2% annually and 18% overall in the decade from 2010 to 2019. While pandemic-related travel restrictions in 2020 briefly set back transport CO2 emissions to 2012 levels, emissions have since resurged, returning to or exceeding pre-pandemic levels for most transport modes once mobility restrictions were lifted and as travel demand and commuting increased. This has resulted in a worrying return to business-as-usual rather than in a much-needed low-carbon pathway (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Changes in CO2 emissions by sector, 2010-2021

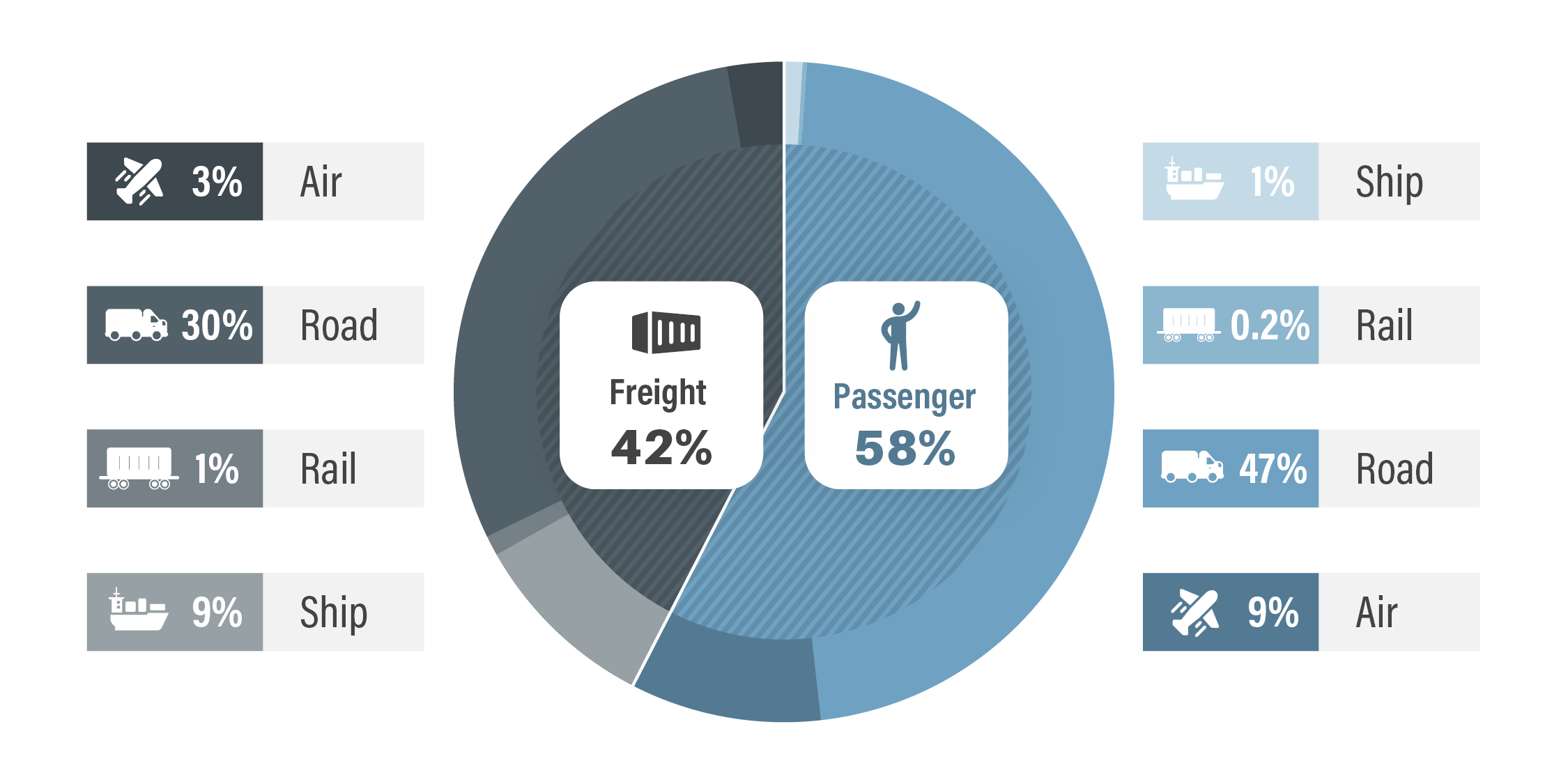

Because of its near-complete dependence on fossil fuels – which supply 95% of the energy demand in transport – the sector contributed nearly a quarter (22%) of global fossil CO₂ emissions in 2019. Transport’s share of emissions fell to 20% in 2020 and 2021, but trends suggest that the sector is on track to surpass its pre-pandemic emission levels. The single largest source of transport emissions continues to be passenger road transport (47%); across all transport modes, passenger transport accounts for 58% of emissions, compared to 42% for freight (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Transport CO2 emissions by activity and mode, 2019

The continued growth in transport emissions, both in absolute and percentage terms, is attributed in part to slow progress in reducing emissions from the “hard-to-abate” sub-sectors of long-distance road freight, aviation and shipping. Transport emissions have increased despite the rapid growth in both renewable energy and electric mobility, due to the overall increase in energy demand (most of it met with fossil fuels) and in the size of the vehicle fleet (mostly non-electric vehicles). Meanwhile, many older, more polluting vehicles remain on the world’s roads because of the large global second-hand vehicle market, with nearly two-thirds of the main importing countries (mostly low- and middle-income countries) lacking regulations to ensure affordable access to higher-quality vehicles.

Ever-increasing passenger vehicle sizes have had a huge direct impact on increasing transport emissions. Vehicle sizes have increased at least 30% and sometimes more than 60% since the 1960s, and even more rapidly in recent years. Sport utility vehicles (SUVs) and large passenger trucks consume around 20% more fuel than a medium-sized car and negate as much as 40% of the recent improvements in vehicle efficiency; SUVs were the only sector – even beyond transport – where emissions increased during the height of the pandemic.

Transport and livelihoods are at growing risk due to more frequent extreme weather events and rising sea levels.

Climate change greatly increases the vulnerability of populations as well as transport systems. Beyond the often heavy human toll, extreme weather events can also have severe impacts on transport-related infrastructure. More than a quarter of the world’s road and rail assets are exposed to at least one cyclone, earthquake or flooding hazard annually. Ports are even more exposed to climatic events, with estimates indicating that 86% of ports globally are exposed to three or more hazards per year. In aviation, around 7% of the flight delays in the United States in 2020 were related to extreme weather events. Sea-level rise is anticipated to increase traffic congestion and to lead to increased flooding and damage to transport infrastructure.

Natural hazards contribute to huge financial losses, leading to an estimated USD 15 billion annually in direct damage to transport systems worldwide. Of this damage, an estimated USD 8 billion occurs in low- and middle-income countries, which experience the highest costs relative to their GDP. Businesses in these countries experienced USD 107 billion in annual losses, with the monetary impacts of transport disruptions far exceeding any physical damages to assets. Losses are projected to grow with increasing climate change, reaching USD 5.6 trillion by 2050 for water-related disasters alone for all sectors, including transport.

Recent examples of the growing impacts of climatic events include the damages from flooding in Pakistan in 2022, and the sandstorm that grounded the Ever Given container ship in 2021, nearly halting international trade. In addition to their toll on lives and livelihoods, such incidents highlight the vulnerability of the transport sector to extreme weather. As climate change contributes to more frequent and intense extreme weather, disaster events are expected to increase.

Access to transport services, in particular public and informal transport, is threatened by extreme weather events and sea-level rise. Extreme weather has been shown to hinder public transport use, and in many places the existing infrastructure available to protect users is inadequate. Rising sea levels negatively impact people’s access to transport and to basic goods and services, for example by leading to increased flooding or by damaging public transport infrastructure. Some scenarios for high sea-level rise estimate that these impacts could increase up to 1,000% in some places by 2100 if emissions are allowed to increase unabated.

International financial institutions are highlighting climate risks in infrastructure, which is producing more resilient transport investments; however, a huge gap remains to bring adaptation finance to the necessary levels. The estimated need for adaptation finance in low- and middle-income countries is 5 to 10 times greater than the current investment. National and sub-national actors – including governments, businesses and civil society – have begun to nominally address climate adaptation and resilience for transport, but concrete action and expenditures remain insufficient.

Drastic action is urgently needed for the world to stand a chance of achieving its climate and sustainability goals.

The transport sector is not on track to achieve its global climate and sustainability goals. Drastic reductions in transport emissions and improved access to integrated transport systems worldwide are urgently required to achieve decarbonised pathways. Doing this will require not only adequate investments in transport adaptation and resilience, but also the repurposing of funds currently going into fossil fuel subsidies as well as an acceleration of investments aimed at achieving transport system transformation.

Continued inaction or incremental action will have dire consequences, pushing out of reach a liveable and equitable future that avoids the worst effects of climate change. The moment for immediate, comprehensive and radical action is now. (See Box 1. Divergent scenarios.)

Box 1: In a time of global uncertainty, we face three divergent scenarios for climate action in the transport sector:

Scenario 1

Abandon meaningful climate action in the transport sector and follow a business-as-usual approach to mobility patterns and investment trends (projected to yield a temperature increase of 4+ °C).

Scenario 2

Continue incremental progress on transport mitigation and increase the focus on adaptation, even though this has shown limited progress over the past 40 years despite economic booms and rapid growth (leading to an increase of 2-4 °C).

Scenario 3

Accelerate radical action on infrastructure and investments to support changing transport operations and behaviour, while prioritising the triple impacts of transport decarbonisation, job creation and equitable access, for a healthier population and planet and a more vibrant and resilient economy and infrastructure (leading to an increase of 1.5-2 °C). scenario).

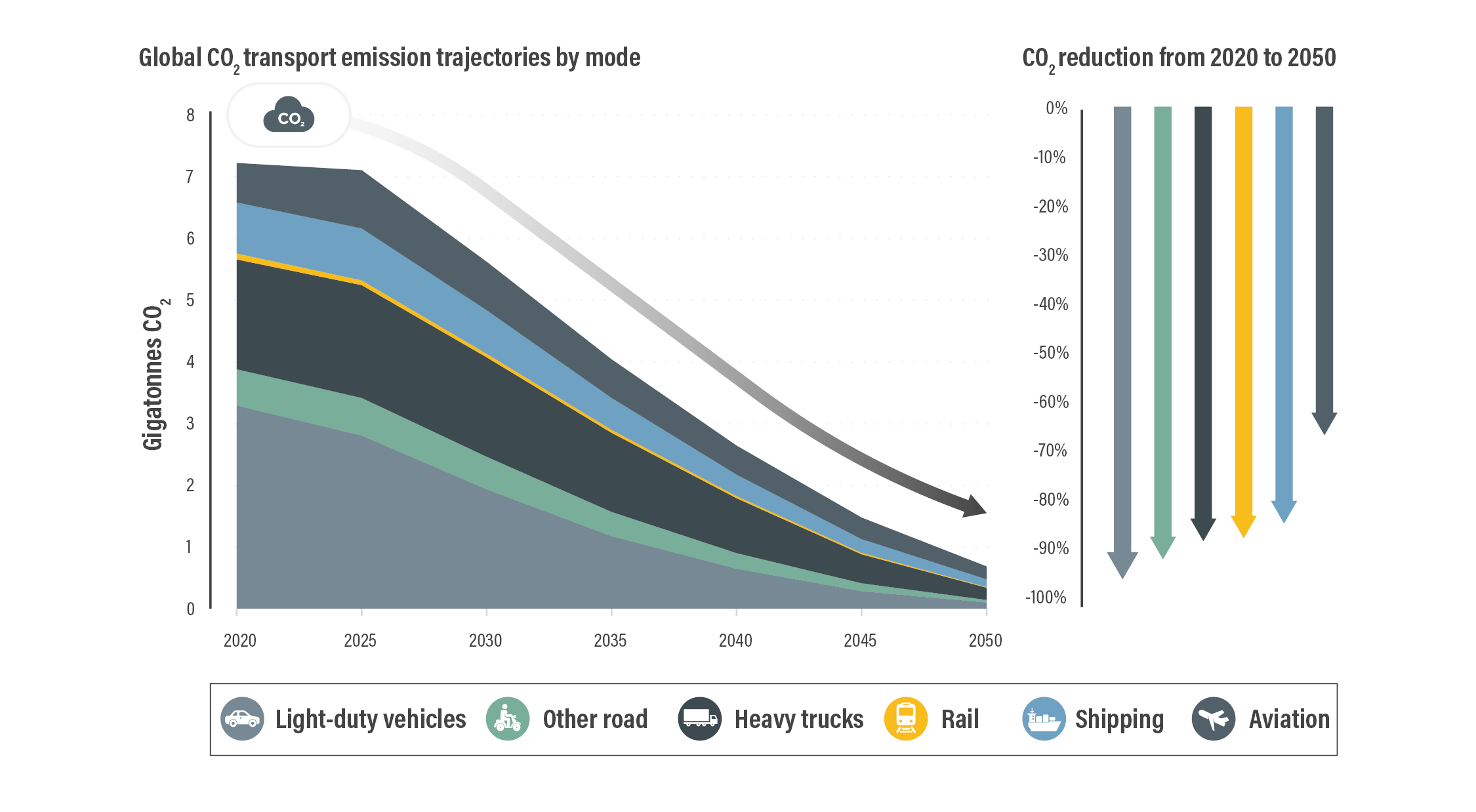

Achieving transport pathways that limit global warming to below 1.5 degrees Celsius (°C) will require a 59% reduction in global transport CO₂ emissions by 2050, compared to 2020 levels. Meanwhile, meeting the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) scenario for net zero emissions by 2050 will require a 90% reduction in transport CO₂ emissions from 2020 levels. Overall, the carbon intensity of the energy used in transport, and of the fuels consumed, needs to be halved by 2050, with the greatest cuts required in road transport (see Figure 3).

Stronger reductions are required in high-income countries – which are responsible for the vast majority of the historical emissions from transport – than in low- and middle-income countries. Middle-income countries now contribute nearly the same level of transport CO₂ emissions as high-income countries, and transport CO2 emissions have been growing more rapidly in many middle-income countries. However, high-income countries continue to have much higher emissions per capita.

To address this reality, systemic transformations are urgently needed globally in how people and goods are transported. Significant progress has been seen in some places, but the vast majority of countries still need to dramatically transform their transport systems to become more equitable, affordable, healthy, environmentally friendly and resilient. Although once believed to be the pinnacle of a modern, advanced society and of economic and technological achievement, prosperity, and progress, the car-centric and fossil fuel-based models of development – which conflate ever-increasing consumption with progress – have long since proven to result in higher, more negative externalities and net-negative impacts. In contrast, the more recent people- and access-centred transport models respond to a wider notion of sustainability with economic, societal and environmental concerns at its core.

High-income countries are typically the worst offenders, having been early adopters and promoters of old car-centric models while often ignorant of the damage that this would cause for people, local jurisdictions and the planet. Although current policies and measures in high-income countries remain far from sufficient, many of these countries are increasingly aware that a car-centric path is misguided and are investing greater effort and funding in more sustainable models. As they transform their own systems to be less harmful, high-income countries also must greatly increase their support to low- and middle-income countries to enable them to develop using more sustainable transport models.

Unfortunately, those with invested interests in the antiquated car-centric system have continued to profit from this focus at the expense of people and the environment. At the same time, many decision makers remain under-informed about the benefits of developing transport systems sustainably. Despite having good intentions, they are supporting “lock-in” to the same polluting, congested and less healthy fate as the places now having to work hard to backtrack on their mistakes.

Low- and middle-income countries have the opportunity to avoid this lock-in to unsustainable models and to avoid the misperception that technological solutions alone (such as replacing more polluting vehicles with electric vehicles) are the silver bullet. Growing cities in high-income countries also have this opportunity. Too often the inequitable, unhealthy and unsustainable car-centric model is still the default, and there is a lack of “Avoid” and “Shift” strategies or optimised land-use planning for healthier populations and economies.

Current policy support, actions, commitments and targets expose complacency.

Climate strategies among all stakeholders – including the public and private sectors, the international community and civil society – are still not ambitious enough to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement and the SDGs. Current national policies announced or implemented will still contribute to average global temperature rise of 2.8°C by 2100. Without more ambitious policies towards structural and systemic transformation, transport emissions could grow as much as 50% by 2050.

The Voluntary National Reviews (VNRs) of the SDGs recognise transport as key to implementing these goals, but few VNRs present long-term targets or concrete policy measures or comprehensively address the urgent systemic transformations needed to enable equitable access to transport and mobility for all. In 2022, the share of VNRs mentioning transport fell to the lowest level (86%) since 2017, totalling 36 out of the 42 submitted VNRs. Sustainable, low-carbon mobility is not represented by a stand-alone SDG, but its successful implementation is a crucial element in the achievement of almost every SDG and must therefore be prioritised appropriately in VNRs.

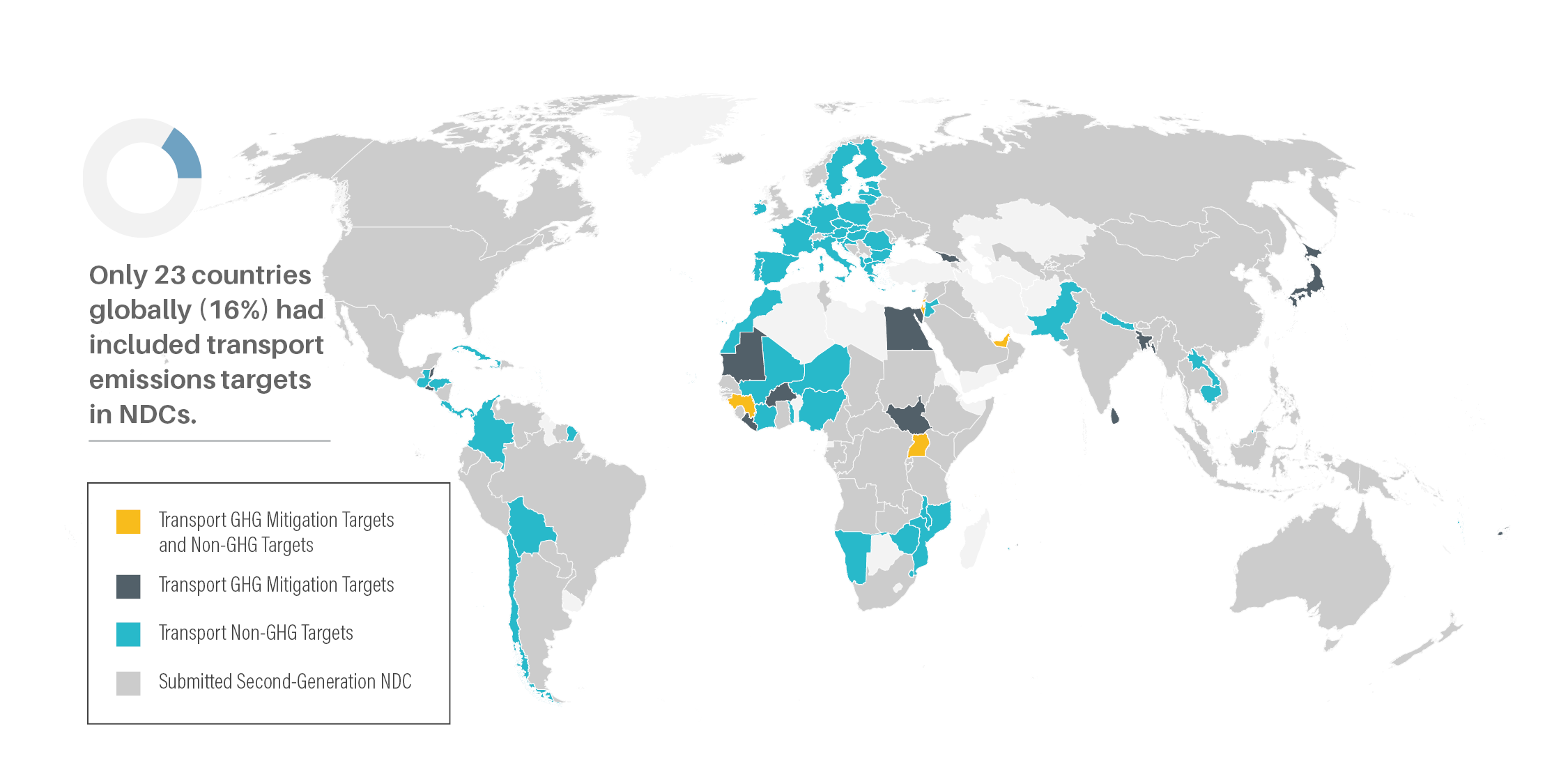

As of 2022, only 23 countries globally (16%) included targets for mitigating transport emissions in their second-generation Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) submitted under the Paris Agreement; this is far from the necessary global commitment. Furthermore, these 23 countries together contribute just 5% of all global transport CO₂ emissions. Although the ambition of these countries is to be applauded, it lays bare the complacency of the other 84% of countries that have neglected to include such targets (see Figure 4). Even if all of the 23 countries meet the greenhouse gas mitigation targets included in their second-generation NDCs, transport CO₂ emissions in these countries would still increase 11% by 2030.

Figure 4. Transport targets, by type, in second-generation NDCs

In NDCs and national transport planning alike, there remains a lack of comprehensive and balanced policy action among national governments, with a disproportionate focus on “Improve” measures. Current plans are focused mainly on passenger transport (mostly electric vehicles) and largely lack attention to hard-to-abate sectors and “Avoid” and “Shift” strategies. Even among “Improve” measures, only a fraction of governments have adopted ambitious policies.

As of 2022, only 23 countries had targets for a 100% ban on sales of internal combustion engine vehicles; only 5 countries also had targets for 100% renewable power (effectively ensuring the use of clean power for electric vehicles); and 5 countries had fuel economy standards that apply to heavy-duty vehicles. Although electric vehicles are part of the solution (alongside “Avoid” and “Shift” measures), a wider agenda is needed that goes beyond electric cars to address electric two- and three-wheelers, public transport, and freight (particularly in low- and middle-income countries) – and that is aligned with the energy transition towards renewables.

National governments often have been lax in enforcing measures, giving too little support to adaptation and access strategies, and too little autonomy and authority to sub-national governments. For many sub-national governments (both local and regional), the lack of support greatly influences their ability to implement sustainable mobility measures as well as plans for net zero greenhouse gas emissions. Urban transport contributes 40% of global transport emissions, and local governments are uniquely placed to lead the transformation within their cities, but many cities are not delivering. Most cities continue to move in the direction of more pollution and congestion and net negative impacts of the car-centric model.

Cities often face funding constraints in implementing sustainable transport measures due to reliance on inadequate revenue streams, subsidies and budget allocations that favour the expansion of road infrastructure. Many strategies for diversifying revenue and re-adjusting priorities can be found in newer, more sustainable models, but these remain underutilised by most cities. As of 2022, just over an estimated 3% of cities worldwide had a low-emission zone in place or planned; only around 10% of cities had a sustainable urban mobility plan (SUMP), and only 20% of sub-national governments had set any net zero target.

In the private sector, some businesses have demonstrated increased momentum in climate leadership in recent years, but collectively this remains insufficient to achieve a 1.5°C pathway. Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement, more companies have set emission reduction targets, disclosed climate-relevant information and developed climate transition plans. However, a CDP study found that up to 74% of the plans of 930 transport service companies worldwide lacked credibility, missing coverage of key elements such as governance, financial planning, value chain initiatives, targets and emission accounting with verification. Many companies have been inconsistent in their advocacy, at times supporting climate action while in parallel undermining or even opposing ambitious policies through powerful lobbying efforts – including many auto manufacturers from Europe, Japan, the Republic of Korea, and the United States, as well as aviation companies.

There is a clear business case for investing in cleaner solutions. For example, a Climate Group study found that based on current market trends that show growing consumer uptake of electric vehicles, a plausible scenario would see electric vehicles comprising the majority of new vehicle sales by 2032. Furthermore, the clean energy market is expected to outpace that of fossil fuels in 2023, meaning that continued investment in polluting fuels and technologies and unsustainable transport solutions means increasing the risks of diminished return on investment and stranded assets.

Partnerships and the international community more broadly have an important role to play. During the 2021 UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, United Kingdom (COP 26) and the 2022 UN Climate Change Conference in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt (COP 27), stakeholders launched and strengthened an unprecedented number of commitments and initiatives on sustainable, low carbon transport. However, there was a notable lack of emphasis on the central role of public transport and walking and cycling (the main mobility modes of billions of people worldwide) in decarbonising transport and building more equitable societies.

Intergovernmental organisations must start leading by example, repurposing support away from unsustainable transport endeavours and critically reassessing their own practices and operations. For example, 57% of the total CO₂ emissions from the UN system in 2020 were from transport, more than three-quarters of which were from air travel, yet most attention in this sector has been on emission offsetting as opposed to changing system-wide practices.

Capacity development and support programmes play a critical role in addressing the many challenges facing the transport sector and are key to achieving a just transition, from ensuring integrated planning to fostering inclusive and equitable human development that is in harmony with nature. However, to achieve meaningful and lasting impact, existing capacity development programmes should be re-evaluated to identify gaps and tailor interventions to meet the evolving needs of professionals, government authorities and other stakeholders. Growing economies in low- and middle-income countries and an expanding global population in general mean that further efforts will be needed to ensure better access to goods and services for all, as well as jobs supporting a more sustainable future.

Scaling up investment and financing and repurposing subsidies: The way forward.

Increasing the level of investment and shifting existing investment practices and subsidies are crucial. Tracked climate financing averaged USD 585 billion annually during 2019 and 2020, or less than a quarter of the estimated amount required to achieve global goals. Despite significant pledges to increase multilateral financing, only a small share of funds cover transport decarbonisation projects. The far-reaching economic effects of the recent global crises have further threatened to hinder the investments needed for low-carbon pathways, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

International finance and investments from development financial institutions specifically for the transport sector increased from USD 136 billion in 2017-2018 to USD 169 billion in 2019-2020, but this is still far short of what is needed. Estimates have found that fully decarbonising the shipping industry alone would cost up to USD 1.9 trillion, achieving net zero CO2 emissions in the aviation sector by 2050 would cost at least USD 5 trillion, and achieving the goal of keeping global temperature rise within 1.5°C by 2050 through improvements in the efficiency of road transport would cost USD 3 trillion. Public budgets often are strained, and what resources do exist are often misdirected towards unsustainable models. This demonstrates the need to reassess funding priorities and to explore new opportunities for mobilising large-scale private investment towards more sustainability objectives.

Meanwhile, fossil fuel subsidies have continued to grow, rising 27% in 2021 to USD 227 billion. Repurposing the funds that go into fossil fuel subsidies towards more sustainable, low-carbon transport models is a must. The World Bank estimates that countries’ expenditures on subsidising fossil fuel consumption are six times greater than the amount pledged in commitments under the Paris Agreement. At the same time, the World Bank spent nearly USD 15 billion on fossil fuel projects since the signing of the Paris Agreement, demonstrating how entrenched unsustainable development models are in the global system, as well as the fact that radical change is needed across all stakeholders, including intergovernmental organisations.

Increased resources for transport adaptation and resilience will be particularly crucial in countries that are most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, notably low- and middle-income countries. Governments, businesses and others have begun to nominally address adaptation and resilience for transport, including through National Adaptation Plans and public-private partnerships, but adequate integrated action and investments are still missing. As of October 2022, only 8% of the Green Climate Fund was invested in transport, with an even smaller share invested in adaptation for transport. Large investments are needed to improve weather- and climate-proof attributes of transport services to maintain basic access.

The transformation of transport systems will not happen overnight, but the end result will be worth it.

Very few of the transport challenges being highlighted today are new

These same messages have been repeated over the past 2-3 decades or more. The world has gone through multiple crises and will likely encounter many others in the future. But there is solid evidence that the climate and inequality crises are enduring ones – and also that the climate and inequality crises are ones where we already have a high number of applicable tools to reach the solutions.

Much has been learned along the way

We have learned that marginal and incremental progress, small policy adjustments and low-ambition targets are not enough.

We have fully demonstrated our ability to make excuses, to postpone action, to refuse to support others in need.

We have seen that some stakeholders do whatever they can to deliberately withhold progress, often even at the risk of harming people and the planet.

We have seen other stakeholders rise to the occasion and become the leaders, visionaries and change makers.

We have seen that some countries understand the meaning behind “just transition” of the transport sector and have refused to leave behind the most vulnerable.

We have seen some cities adopting more sustainable models and prioritising access to transport and mobility services for all.

We also have learned that governments can act overnight in redirecting policies and funding when they choose to, as seen during the pandemic and the ongoing energy crisis.

We already know what is needed – all that is missing is action at the scale and speed required.

All stakeholders, across the board, must revolutionise their level of ambition, action and accountability towards the structural transformation of transport systems.

Governments must make climate strategies dramatically more ambitious and actionable, repurpose funds currently supporting fossil fuels, enable more sub-national action, ensure an equitable and just transition, and send clearer signals and incentives to the market.

Businesses must end counterproductive lobbying, implement credible climate transition plans, and redirect investments from polluting endeavours, most notably fossil fuels and ever-larger vehicles.

International finance and development institutions, including multilateral development banks, must lead by example, scaling up efforts towards sustainable transport systems, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, in line with international climate and development goals.

The global transport community and civil society can lead and support in many efforts, from conducting research, capacity building programmes, and outreach campaigns, to increasing the pressure on governments and businesses, to countless other invaluable roles.

At a minimum, to transform our transport and mobility systems, we know we need to:

- Implement integrated, inter-modal and multi-dimensional approaches across passenger and freight transport.

- Put walking, cycling and public transport at the heart of passenger transport strategies, and end the unsustainable car-centric model.

- Increase vehicle efficiency and reduce vehicle size and volume.

- Expand the uptake of electric vehicles beyond cars and increase charging infrastructure.

- End fossil fuel dependency in transport and increase the uptake of renewable energy, with policies that support an equitable and just transition.

- Scale up financing for sustainable, low carbon transport solutions and redouble efforts on the adaptation and resilience off transport systems.

- Repurpose funds currently going towards fossil fuels subsidies in transport or other polluting activities.

- Fill the capacity needs to harness opportunities, ensuring a just transition and equitable access to transport, jobs and services.

- Improve data and data literacy.

- Mobilise multi-stakeholder action and ambition.

The end result will be worth it. What are we waiting for?

A drastic shift from the status quo will be necessary to achieve a systemic transformation of transport and mobility, but evidence has repeatedly shown that these changes will come with society-wide positive impacts, delivering cross-cutting solutions at the nexus of equity, climate, health, energy, urban planning and economic development.

Collective, active and electrified transport is key for a more equitable, accessible, healthy, green, sustainable and resilient transport future.

This transformation of transport is an enormous opportunity for more inclusive, prosperous, healthier, greener and resilient communities. What will it take for decision makers to step up and deliver the level of change that is necessary? What additional evidence is needed to convince us that a future based on our current trajectory towards 2.8°C of global warming is not “the best we can do”? What will future generations say about our inaction, our short-sightedness, our greed and our carelessness in implementing sustainable, low carbon transport approaches for people and the planet?

Decision makers have the choice: The transport sector can continue to be part of the problem, or it can change course and lead the solution.

What are we waiting for? What are you waiting for?

Despite advances, trends have revealed glaring gaps in climate and sustainability action for transport.

Current targets, pledges and actions have at times given the illusion of progress, causing a sense of complacency. In reality, the gap is still exceedingly apparent in terms of progress on both climate change and sustainability for the transport sector. Selected trends, outlined here from A to Z, reveal that despite some progress, advances are moving far too slowly.

Note: These are selected highlights from the SLOCAT Transport and Climate Change Global Status Report – 3rd edition. See cross-referenced sections for more detail, as well as the Key Insights, all available at www.tcc-gsr.com:

- Module 1: Transport Pathways to Reach Global Climate and Sustainability Goals

- Module 2: Regional Trends in Transport Demand and Emissions, and Policy Developments

- Module 3: Climate and Sustainability Responses in Transport Sub-Sectors and Modes

- Module 4: Transport and Energy

- Module 5: Enabling Climate and Sustainability Action in Transport: Finance, Capacity and Institutional Support

A

Access

+ Some cities are leading the way on increasing access, such as Barcelona (Spain), which made 92% of its subway system wheelchair accessible as of 2019, with a goal to reach 100% by 2024; Seattle (USA), where the public transport system was deemed 100% accessible by 2022; and Cape Town (South Africa), which is considered one of the most wheelchair-accessible cities in Africa.

– The implementation of access measures remains fragmented and often incomplete, and many places continue to lack basic access to goods and services, as well as supporting accessibility infrastructure. (See Module 3.1. Integrated Transport Planning.)

Adaptation

+ Stakeholders have begun addressing the need for adaptation through National Adaptation Plans and public-private partnerships.

– The estimated gap in adaptation finance for low- and middle-income countries is 5 to 10 times greater than current levels.

– Only 8% of the Green Climate Fund was invested in transport, with an even smaller fraction invested in adaptation for transport.

Aviation

+ CO₂ emissions from international aviation fell 45% in 2020 due to the pandemic, and although they increased 15% in 2021, they were still 37% below 2019 levels.

+ Efforts to rein in emissions through measures such as sustainable aviation fuels, hydrogen and electrification have shown some early promise.

+ In 2022, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) adopted a long-term aspirational goal of net zero carbon emissions for international aviation by 2050.

– Emissions from aviation continue to increase and at a faster rate than other transport sub-sectors.

– Technological advances remain far from the required scale to have a significant impact.

– The lack of binding commitments and interim targets in the ICAO goal means a lack of incentives for urgent climate action. (See Module 3.7. Aviation.)

Avoid-Shift-Improve

+ A 2021 study in the journal Nature Climate Change found that “Avoid” and “Shift” measures could result in nearly equivalent emission reduction as “Improve” measures.

+ The International Energy Agency found that investing in walking and cycling in particular could have the largest multiplier effect for jobs.

+ “Avoid” and “Shift” measures have been estimated to have the largest net-cost benefits.

+ “Avoid” policies show the biggest potential towards achieving oil independence, followed by “Shift” and “Improve” policies, while “Avoid” measures show greater health, economic, and societal benefits, followed by “Shift” and “Improve” measures.

– “Improve” measures continue to receive most attention while also showing a lack of delivering the required climate and sustainability results, as evidenced by the transport sector being far from its targets.

B

Behaviour change

+ Pandemic-related mobility restrictions and higher fuel prices led to significant changes in travel behaviour, including many positive changes such as increases in walking and cycling.

– Changes also included increases in private car use and decreases in public transport use.

– Governments have not taken sufficient action to reinforce and scale up positive changes through supportive policy and infrastructure.

Business

+ A growing number of companies worldwide across all sectors, including transport, have committed to reducing their emissions and have taken different steps to reduce their emissions and contribute to international goals.

– Collectively, private sector efforts remain insufficient to achieve a pathway that is consistent with the goal of keeping global temperature rise below 1.5°C.

– The lobbying efforts of many companies have run counter to climate and sustainability action, severely undermining progress. (See Module 1.3.3. The Role of Business in Decarbonising Transport.)

C

Cities and local governments

+ Local governments are uniquely positioned to take ambitious action.

+ Many local governments have taken some ambitious steps towards transforming their local and regional transport systems.

+ Some national and regional governments have enabled local authorities to accelerate the uptake of sustainable transport measures.

– Most cities have taken far too little action, in many cases continuing to support the car-centric model and even encouraging sprawl and other unsustainable features.

– Many cities have not set targets that are ambitious enough and/or backed by supportive policy and measures, while many cities that have set targets are not delivering on their pledges or potential.

– Many national and regional governments have not provided cities with the authority and financial support to implement ambitious action. (See Module 1.3.2. Sub-national Actions for Sustainable, Low Carbon Transport.)

Cycling

+ The pandemic was a catalyst for change for cycling, with temporary cycle lanes and pedestrianising streets worldwide to allow outdoor activity while maintaining social distancing, in some places removing on-street parking spaces.

+ In many cities, such changes were made permanent due to their popularity.

+ The global bicycle market grew 14% between 2021 and 2022, from USD 38.4 billion to USD 43.8 billion, with global e-bike sales expected to reach USD 62.3 billion in 2030.

– The vast majority of roads worldwide remain unsafe for cyclists, and in 2019 a total of 41,000 cyclists died in road traffic-related crashes worldwide. (See Module 3.3 Cycling and Module 3.1 Integrated Transport Planning.)

E

Energy

+ Renewable energy use has expanded rapidly, particularly in the power sector, and promising improvements have been made in vehicle technology and efficiency.

– The share of renewables in the global energy mix has increased only slightly, due to rising overall energy demand; transport is a major culprit, accounting for one-third of total global energy demand.

– Transport’s renewable energy share has remained virtually unchanged over the past decade, at just over 3%, despite ongoing efforts.

– The increased popularity of SUVs and trucks is outweighing any energy efficiency savings. (See Module 4.1 Transport Energy Sources.)

F

Finance

+ New initiatives were launched during 2022 and 2023 as a call to the international community for greater financial support for low- and middle-income countries affected by climate change, as well as for reforms to international climate finance to help enable the transition.

– Funds for transport adaptation and resilience remain far from the levels needed.

– Many countries are already experiencing climate-related impacts on their transport systems and infrastructure, which are projected to worsen if climate change continues unabated. (See Spotlight 2. Transport Adaptation, Resilience and Decarbonisation in Small Island Developing States and Module 5.1 Financing Sustainable Transport in Times of Limited Budgets.)

Freight

+ The recent multiple global crises and supply shortages increased awareness of the need to prioritise more local and regional production and consumption.

– These events also demonstrated the fragility of global supply and logistics chains and their international interdependencies.

– Global freight activity is projected to double between 2019 and 2050, which could mean that CO₂ emissions from freight transport would be 22% higher in 2050 than in 2015, with rising demand for deliveries and transport of goods, longer supply chains, and less regulations in support of efficiency improvements. (See Spotlight 4. Shortening Global Supply Chains as a Key to Decarbonising Transport and Module 3.6 Road Transport.)

G

Gender

+ Some places have put in place measures to increase security for people of different genders in public transport systems.

+ Several countries – including Brazil, Egypt, Indonesia and Mexico – have addressed women’s concerns for safety on board by reserving the front of buses or metro carriages for women and children, with the police responsible for enforcement.

– Women and girls face increased risk of harassment or personal safety concerns on public transport, as do transgender and non-binary people, which is often heightened in low- and middle- income countries.

– For rural households in the lowest-income countries, the burden of transport is estimated to be four times greater for women than men, and women carry an estimated 90% of the physical burden. (See Module 3.1 Integrated Transport Planning and Module 3.4.1 Public Transport.)

H

Health

+ The planning of healthy cities strongly favours public transport and active mobility, and the health benefits from reduced car dependence are increasingly influencing urban planning processes.

+ The pandemic led to heightened awareness of the relationship between urban settings and people’s exposure and vulnerability to health risks.

– The needed improvement of public transport, walking and cycling to reach health outcomes is still getting far less attention than required. (See Spotlight 1. Transport-Health Nexus.)

I

Informal transport

+ Informal transport moves millions of people, employs hundreds of thousands and supports urban economies; it is present in nearly every city and town in low- and middle-income countries, with the potential to accelerate the transition towards sustainable transport systems.

– Attempts to incorporate informal transport into global and local decarbonisation efforts have been hampered by the lack of consolidated and robust information.

– There has been a tendency to ignore or eliminate informal transport, which has generated large gaps in policy, knowledge and data.

– During the pandemic, informal transport services experienced up to 50-70% losses in demand and income, with little to no support from government. (See Module 3.4.2 Informal Transport.)

Integrated transport planning

+ Integrated transport planning has received increasing attention in recent years, particularly as the pandemic created an opportunity to rethink transport in cities.

– Integrated transport planning remains largely underutilised, as do other similar strategies for addressing the interconnections between transport, land use and other factors to support the creation of sustainable transport systems. (See Module 3.1 Integrated Transport Planning.)

J

Just transition

+ Ensuring a “just transition” has gained increasing prominence in recent years, and many places have implemented policies and programmes to support workers during the changing circumstances necessary as part of climate action.

+ There is significant job creation potential in sustainable transport.

– Commitment to a just transition is lacking in both the public and private sectors, and many workers have not received sufficient support.

L

Low-emission zones

+ Several cities and countries around the world have deployed low-emission zones (LEZs), ultra-low-emission zones (ULEZs), zero-emission zones (ZEZs), and ZEZs specifically for freight vehicles (ZEZ-Fs).

+ The use of designated zoning can lead to reduced CO₂ emissions and improved health and social equity.

+ As of 2023, such zones were most present in Europe, with the number of active LEZs in Europe having increased 40% between 2019 and 2022, though developments in LEZs elsewhere have expanded to China, India, and Indonesia.

– In some cases, deployment has faced public opposition, enforcement difficulties and challenges in establishing clear criteria for determining vehicle eligibility. (See Module 3.1 Integrated Transport Planning.)

M

Maritime shipping

+ Shipping emissions have remained relatively stable.

+ In 2023, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) adopted a revised strategy to address greenhouse gas emissions from the maritime shipping sector, including targets to reduce emissions up to 80% below 2008 by 2040, compared to 2008 levels, which would keep the sector within the carbon budget required to limit global temperature rise within 2°C.

– Shipping emissions are still significant, accounting for 10% of transport CO₂ emissions by 2019 and producing more transport CO₂ emissions than Africa and Oceania combined.

– The IMO goal would be insufficient to support a 1.5°C goal and includes no clear strategy to achieve its target. (See Module 3.8 Shipping.)

P

Public transport

+ Defying budget cuts and low ridership, public transport expansion projects continued during 2020-2021 in all major regions.

+ Public transport ridership recovered relatively quickly from pandemic-related drops in usage in parts of Asia, South America, and Africa, even surpassing pre-pandemic levels in some places.

+ The pandemic reinforced the necessity of public transport in cities, not only for mobility and equity but also to reduce emissions and to prevent a shift to private vehicles.

– Public transport systems in North America and Europe continued to suffer from decreased ridership into 2023, accompanied by lower revenue and difficulty maintaining the same level of reliable services for essential workers and those who rely on public transport for daily mobility.

– Gender and safety continue to be an issue, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

– Low- and middle-income countries continue to have limited access to public transport. (See Module 3.4.1 Public Transport.)

R

Rail

+ Rail is considered to be the cleanest mode of collective passenger transport, due to high rates of electrification and energy efficiency, and has the highest share of renewable energy use among all sub-sectors thanks to its high electrification rate.

+ Operators around the world are upgrading their rail fleets.

+ High-speed rail has great potential to replace car trips and shorter flights, with the global network expanding by more than one-third from 2017 to 2022.

– Rail is highly vulnerable to global shocks and geopolitical instability.

– The modal share of rail is still limited; despite growing demand from 2010 to 2020, only 6-7% of passenger journeys were made by rail. (See Module 3.5 Rail.)

Resilience

+ Building resilience in transport can support socio-economic resilience to global shocks.

+ Some governments saw the energy crisis as an opportunity to improve resilience through reducing their reliance on imported fossil fuels by increasing support for renewable energy, energy efficiency and energy conservation.

– Many countries have pushed for domestic fossil fuel production and new infrastructure to support LNG imports in the face of the energy crisis.

Road transport

+ There have been many decarbonisation efforts and targets for road transport, and the efficiency of road vehicles has vastly improved over the past few decades.

+ By 2022, 23 countries and 17 sub-national jurisdictions had targets for 100% bans on sales of internal combustion engine vehicles, while some governments have discouraged building new roads.

– Emissions from road transport have continued to increase over the past two decades with little sign of slowing, while the health and social cohesion benefits of less-private-car-dependent mobility systems remain untapped.

– During the height of the pandemic, emissions fell across all sectors (even beyond transport) except for one: SUVs.

– Vehicle sizes continue to increase due in large part to increased marketing efforts by automobile companies, which benefit from higher profit margins with larger vehicles, sometimes nearly double the price of comparable smaller vehicles.

– Increased vehicle sizes mean increased space devoted to vehicles, which can be up to 60% of city centres.

– Congestion pricing has only been implemented in a few cities around the world, and roads continue to be built and expanded despite evidence showing that this will increase traffic. (See Module 3.6 Road Transport.)

S

Second-hand vehicles

– Two-thirds of the main importing countries have weak or very weak policies regulating importation.

+ Countries that implemented measures to regulate importation – in particular age and emission-related standards – were able to ensure better access to higher-quality vehicles, including electric and hybrid vehicles.

Shared mobility services

+ Since 2020, the demand for shared mobility services has trended upwards, following a reduction during the lockdowns of the COVID-19 pandemic.

+ Global increases have occurred in the number of carsharing, ride-hailing, and micromobility users as well as the number of cities offering carsharing services.

– Some places have taken steps to make such services less available, in some cases even banning them. (See Module 3.4.3 App-Driven Shared Mobility.)

Sustainable Urban Mobility Plans

+ In a growing number of cities, mostly in Europe but also across Africa, Asia and Latin America, sustainable urban mobility plans (SUMPs) have been adopted to promote sustainable modes of transport and reduce the negative impacts of urban mobility.

– Although some national governments have adopted laws mandating that cities have a SUMP, actual adoption of SUMPs has been delayed in some cases.

– Many SUMPs are far from comprehensive, lacking adequate strategies for implementation, and do not consider key sustainability aspects such as health and equity. (See Module 3.1 Integrated Transport Planning.)

T

Teleworking

+ Increases in teleworking have endured even after the height of the pandemic, contributing to a decline in motorised travel (and therefore emissions), with surveys showing that the trend has continued to some extent in much of the world.

– While telecommuting reduces work-related travel, studies have indicated that this could be offset by counter-effects such as increased private travel and non-work-related energy use.

– A divide between income groups became more apparent across several regions during the pandemic, as people in more affluent urban areas could more easily telework and have goods delivered. (See Module 3.1 Integrated Transport Planning.)

W

Walking

+ Walking can deliver progress towards more of the Sustainable Development Goals than any other transport mode.

+ On average, an estimated 20-30% of all trips globally are walked, as are 85% of all trips to and from public transport.

+ In 2022, some cities in high-income countries saw very high shares of walking, reaching 47% of trips in London (UK) and Paris (France); many cities in low- and middle-income countries had even higher shares, in some cases because of having no alternatives.

– Pedestrians accounted for 36% of the 264,526 people killed on African roads in 2019, and for 38% of the 25,908,698 global road traffic injuries.

– It is the countries where people walk the most – in low- and middle-income countries – where the value, commitment, policy and budgets are often lowest.

– Walking is not sufficiently valued, planned for or invested in countries across the world, nor in the wider climate agenda.

– In 2022, only 42% countries had a national walking policy, while 52% countries had sub-national policies. (See Module 3.2 Walking and Module 3.1 Integrated Transport Planning.)

Z

Zero (tailpipe) emission vehicles

+ Electric vehicles have zero emissions at the tailpipe and produce far fewer greenhouse gas emissions over their lifetimes than internal combustion engine vehicles. They can help improve local air quality, lower transport costs, and work as a driver of fossil fuel phase-out, and even energy access through vehicle-to-grid applications and batteries having a secondary function as energy storage.

+ Electric four-wheel vehicles are the fastest growing sector of the clean energy industry by revenues, whereas electric two- and three-wheelers and electric-assist bikes have seen greatest growth in numbers.

– Electrification of heavy-duty vehicles has had a slower start compared to light passenger vehicles.

– Increased electrification of vehicles could risk a larger divide between poor and rich nations, and it will not resolve several critical transport issues, such as accessibility for the many, traffic congestion, road safety, urban sprawl and the amount of public space devoted to vehicles.

– The overall share of electric vehicles in the transport sector remains around 1% due to the continued increase in the overall vehicle fleet (most of which is not electric); renewable energy provides only around one-quarter of the power supply for such vehicles. (See Module 3.6 Road Transport and Module 4.2 Vehicle Technologies.)

Authors: Hannah Murdock, Imperial College London