-

Shipping

- Key Findings

Demand trends

- Maritime trade volumes have increased four-fold in the last four decades, leading to more competitive shipping rates through economies of scale. The maritime shipping industry moves around 11 billion tonnes of goods annually, roughly 300 times more than is moved by aircraft.

- At the beginning of 2023, global container shipping rates were almost back to pre-pandemic levels, defying predictions of the pandemic driving a paradigm shift in container shipping.

- Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the capacity of container shipping fleets was reduced in the Russian Federation, and operations at Ukrainian ports were suspended until July 2022, when grain exports resumed.

- As much as 40% of maritime trade consists of transporting fossil fuels (such as oil, coal and liquefied natural gas, LNG) from points of fuel production to points of fuel consumption. By 2050, global fossil fuel demand is projected to decline 80% for coal, 50% for oil, and 25% for natural gas, which could lead to stranded assets for fossil fuel transport in the shipping industry.

- The average age of the world’s container shipping vessels increased from 10.3 years in 2011 to 13.7 years in 2022. This ageing global fleet is leading to increasing pollution per unit of volume.

- Since mid-2020, higher shipping costs have been driven by events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

- As of 2021, advanced biofuels for shipping cost two to three times as much as conventional fuel and thus were not yet widely commercially viable.

- Inland waterway freight activity in the European Union (EU) increased 3.3% in 2021, with container ship demand rebounding after several years of volatility.

Emission trends

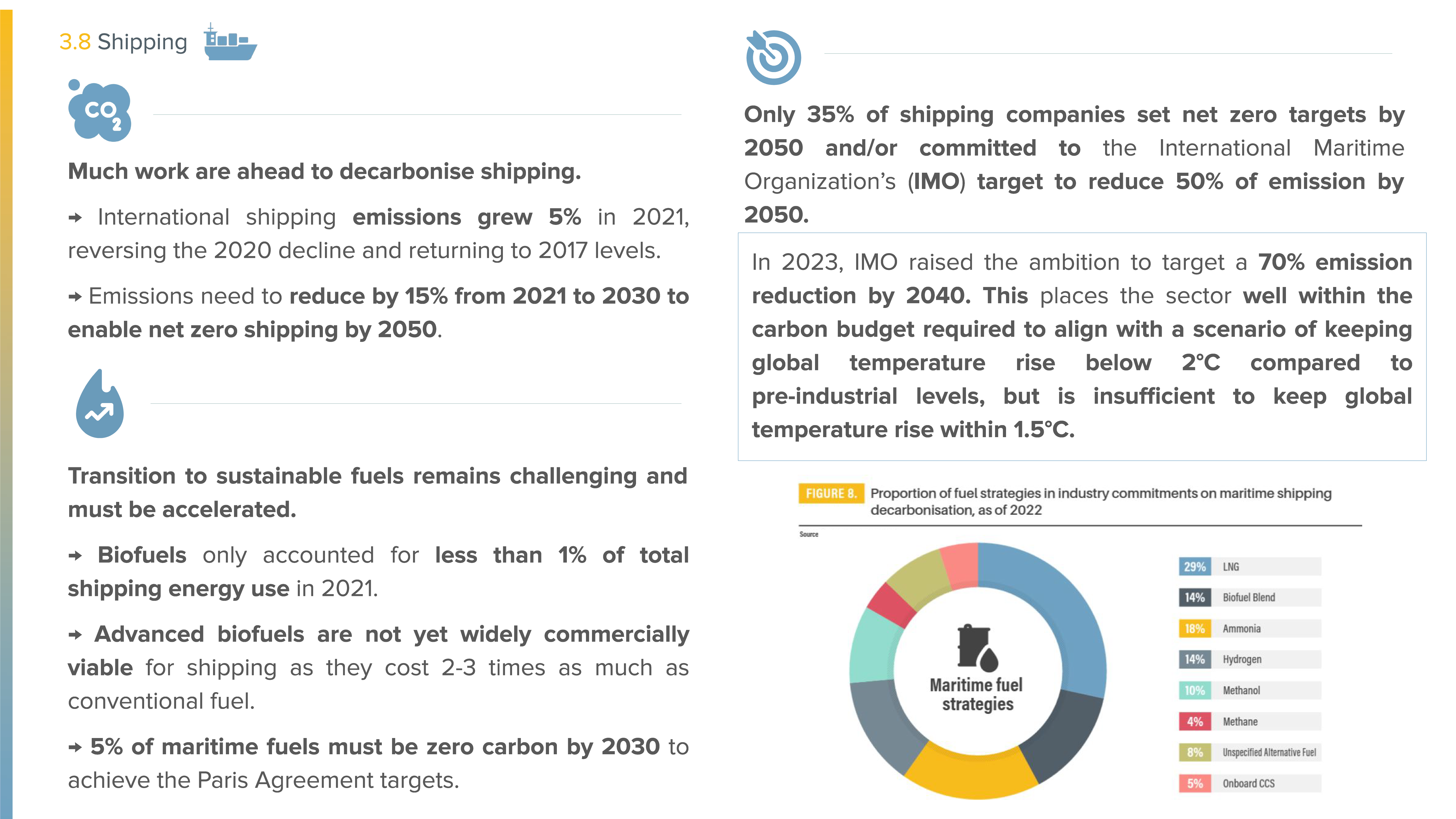

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from the international shipping sector grew 5% in 2021, reversing a decline in 2020 and returning to 2017 levels. CO2 emissions from the world’s maritime shipping fleet grew an estimated 4.7% in 2022 and increased 23.8% overall between 2012 and 2022.

- Although international shipping has the lowest CO2 emissions per tonne-kilometre among transport modes, the sector emitted around 700 million tonnes of CO2 in 2021, a total exceeded by only five countries: China, the United States, India, the Russian Federation and Japan.

- Even in a scenario in which measures taken by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) contribute to lowering emissions, a 15% decline in emissions between 2021 and 2030 is needed to enable the sector to achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

- In 2019, inland waterway transport produced far fewer CO2 emissions than road or rail transport while contributing to several of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Inland waterway transport is responsible for 2% of the global greenhouse gas emissions from transport.

- Roughly 5% of maritime fuels must be zero carbon by 2030 to achieve the targets of the Paris Agreement. As of 2021, however, biofuels accounted for less than 1% of total shipping energy use.

- Sails are making a comeback in decarbonisation pledges, with more than 20 commercial ships using “wind-assist” technologies retrofitted to existing vessels as of 2023. Battery-electric propulsion is emerging as a low-emission option for the marine shipping sector, due to its considerable potential for emission reduction.

- A global carbon price on maritime shipping would create further incentives to accelerate development of biofuels, wind propulsion and battery-electric vessels.

Policy developments

- An IMO submission in 2022 suggests increased ambition towards mitigating emissions, with the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index and the Carbon Intensity Indicator entering into force in 2023.

- In June 2023, the IMO adopted a revised strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from international shipping to at least 70% below 2008 levels by 2040, and striving for 80%. This is a major improvement from the IMO’s initial 2018 strategy, which aimed at a 50% reduction by 2050.

- Overall, the revised IMO strategy raises the level of ambition for emission mitigation and is estimated to place the international shipping sector well within the carbon budget required to align with a scenario of keeping global temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius (°C) compared to pre-industrial levels. However, the strategy remains insufficient to support the carbon budget in a scenario of keeping global temperature rise within 1.5°C.

- The revised IMO strategy does not directly enforce a carbon price for maritime shipping despite earlier IMO working group meetings giving hope for such an economic levy, which was seen as a breakthrough by many Parties to the Paris Agreement.

- As of 2022, only 35% of major maritime shipping companies had set a target for net zero emissions by 2050 and/or had committed to the 2018 IMO target of a 50% emission reduction by 2050. A third of commitments by firms had identified a fuel strategy, with LNG being the most common conventional fuel and ammonia the most common alternative fuel.

- During 2021 and 2022, a varied group of ports, cities, cargo owners, and shipping companies and manufacturers issued commitments and calls for decarbonising the sector by 2050 and making zero-emission vessels widespread by 2030.

- For domestic maritime transport (coastal and inland shipping), very few efforts are in place to support a shift from road freight to inland waterways.

- The Maritime Just Transition Task Force of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change was established in 2021 to facilitate a decarbonised shipping industry, followed by the launch of the Just Transition Work Programme in 2022. Maritime shipping has been identified as one of the “hard-to-abate” sectors targeted under the Mitigation Work Programme adopted in 2022.

-

Emissions from international shipping continue to be outside the scope of countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) towards reducing emissions, due to a lack of clarity in the Paris Agreement.

- With additional cost pressures deriving from the Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine, and despite the new IMO targets, there is a strong risk that shipping decarbonisation will slip further down the policy agenda.

Author: Karl Peet, SLOCAT Secretariat